NLP Project -- Pronounciation Prediction for Teochew Dialect (Part 2)

Welcome to part two of my Teochew NLP project! In my previous post, I explored the tonal relationship between the Mandarin and Teochew dialects using data visualization techniques. This time, I am about to show you some exciting work I did to predict Teochew pronunciation using Mandarin.

If you are interested in seeing how a computer (who is smart enough to understand Mandarin) can learn Teochew from an NLP perspective, this is the right place!

Initials, Finals, and Tones

As I mentioned in my previous blog post, initials, finals, and tones are three essential features for my analysis. But what exactly are they?

Teochew

Let’s first talk about those of the Teochew dialect. In this dataset, Teochew initials and finals adopt syllables in the IPA convention.

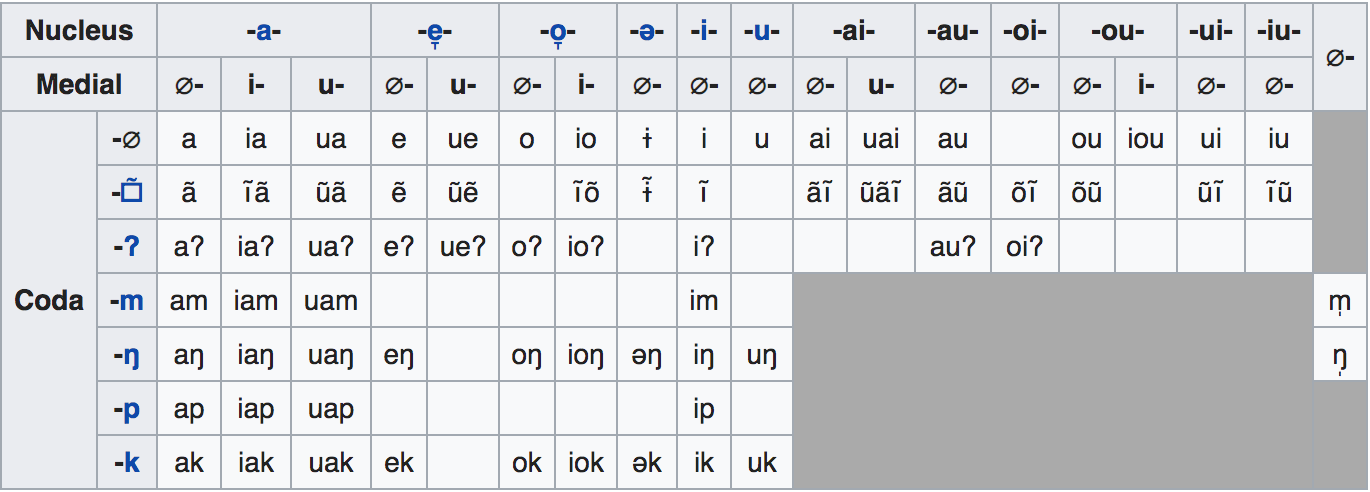

The initial consonant is what we called the initial. There are 18 initials and a few examples of them are m, pʰ, tʰ, p, t, k, b. What follows the initial is called the finals. Teochew finals consist maximally of a medial, nucleus, and coda; however, only a vowel nucleus or a syllabic nasal is minimally required.

Table below is taken from Wikipedia.

Extracting more fine-grained components (medial, nucleus, coda) as features is more desirable; however, it requires extra effort to sort the phonemes into their correct places, as some components are not mandatory in finals. Due to time limits, I chose to treat the finals as one feature, resulting in 73 combinations from the Beida dataset.

There are 8 tones in Teochew, a joke example of this is /tio¹¹ tsiu³³ ue¹¹ ho⁵² oʔ²¹ oʔ⁴/ (Teochew dialect is hard to learn), which consists of six tones. In the dataset, tones are 33(mid), 11(low), 21(low checked), 213 (low rising), 35 (high rising), 4 (high checked), 53 (falling), 55 (high).

People who learn Teochew might notice that the above citation tones become their corresponding sandhi tones when the characters precede another character in a phrase. However, since there is an established mapping from citation to sandhi in the literature, I only attempt to predict the citation tone and not the sandhi.

Mandarin

Mandarin, also called Standard Chinese, comes with a set of syllables known as Pinyin. Like IPA, Pinyin comprises of initials, finals, and tones.

It looks surprising to realize that – many years after I first learned Pinyin in elementary school – Pinyin has some very counterintuitive rules. For example, a vowel ü (pronounce it by making the “ee” sound in your mouth with your lips in the “oo” position) is written as u when it comes after consonants like j, q, x, and y. In some rare cases, for example, ‘女’ (nü), two dots of ü remain to avoid ambiguity from ‘努’ (nu).

I used a tool called xpinyin to convert Chinese characters to Pinyin in the dataset. I then manually transcribed all ü, including those written as u, to v. In evaluation, this helps to check whether a computer predicts a syllable as ü or u. A complete list of Pinyin initials and finals can be found here.

There are five tones in Mandarin, including a neutral tone. In my previous post, I showed a correspondence analysis of tones between Mandarin and Teochew.

Multi-Target Classification

The goal was to explore the one to one correspondence between Mandarin and Teochew. There are 24 unique initials, and 36 finals, and 4 tones found in the Mandarin column, corresponding to 18 initials, 73 finals, and 8 tones in the Teochew column of my dataset. It is natural to treat it as a multi-target classification problem. Our inputs/outputs are initials, finals, and tones from Mandarin/Teochew.

Assumptions About the Data

My baseline is based on a naive assumption; that is, each feature in Mandarin only affects the corresponding feature of Teochew. Under this assumption, Teochew initials, finals, and tones are predicted independently.

Let’s make some plots to see the intuition behind the assumption!

Everyone Appreciates Beautiful Graphs, Huh

1. Tones

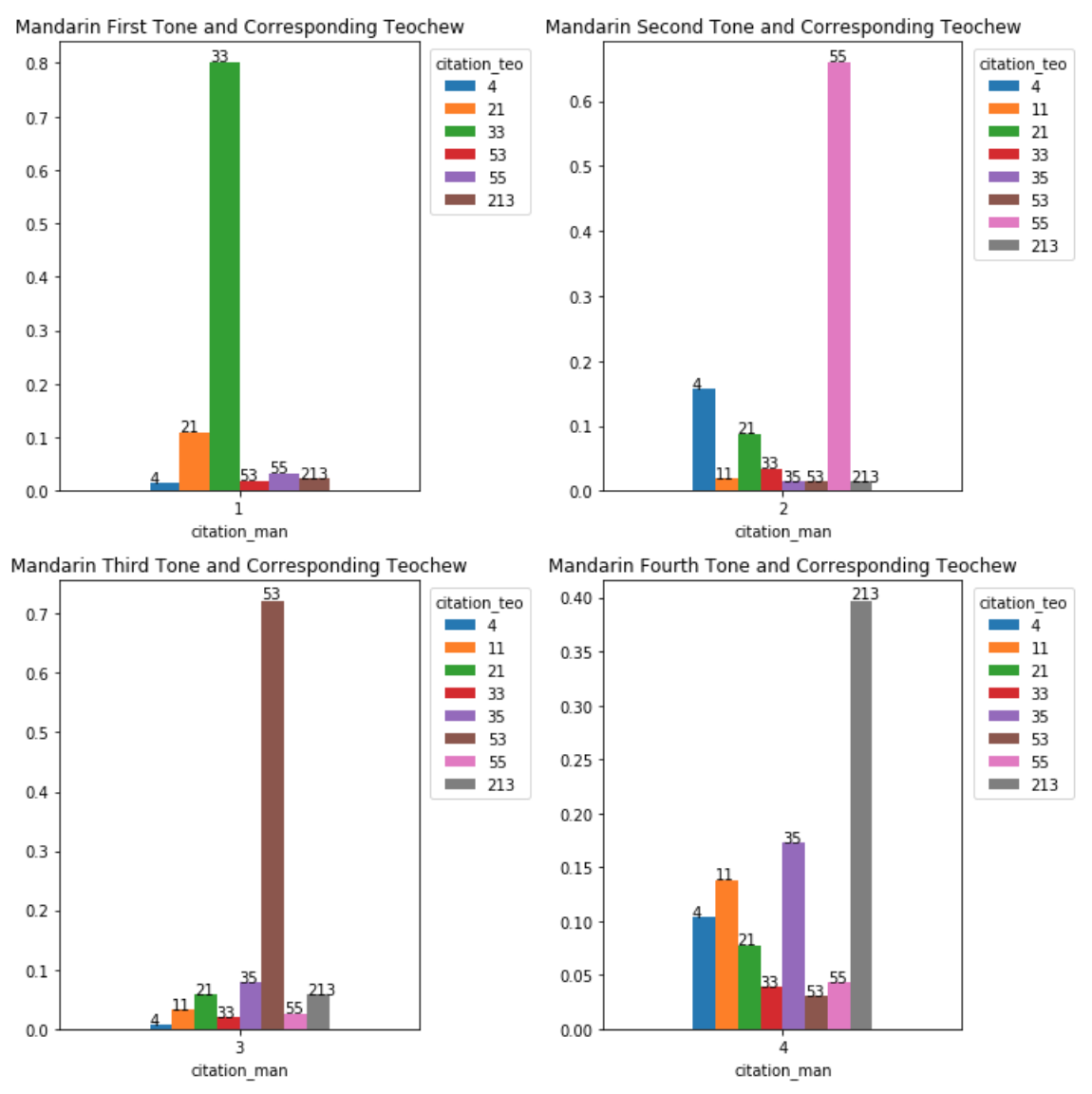

Below are four plots that show the percentage of corresponding Teochew tones for each Mandarin’s.

The first three plots indicate the absolute majority of the corresponding Teochew tones that is over 50 per cent, while the bottom right one has a majority that is under 50 per cent.

Mandarin first tone ![]() Teochew mid tone (33)

Teochew mid tone (33)

Mandarin second tone ![]() Teochew high tone (55)

Teochew high tone (55)

Mandarin third tone ![]() Teochew falling tone (53)

Teochew falling tone (53)

Mandarin fourth tone ![]() Teochew low rising tone (213)

Teochew low rising tone (213)

2. Initials

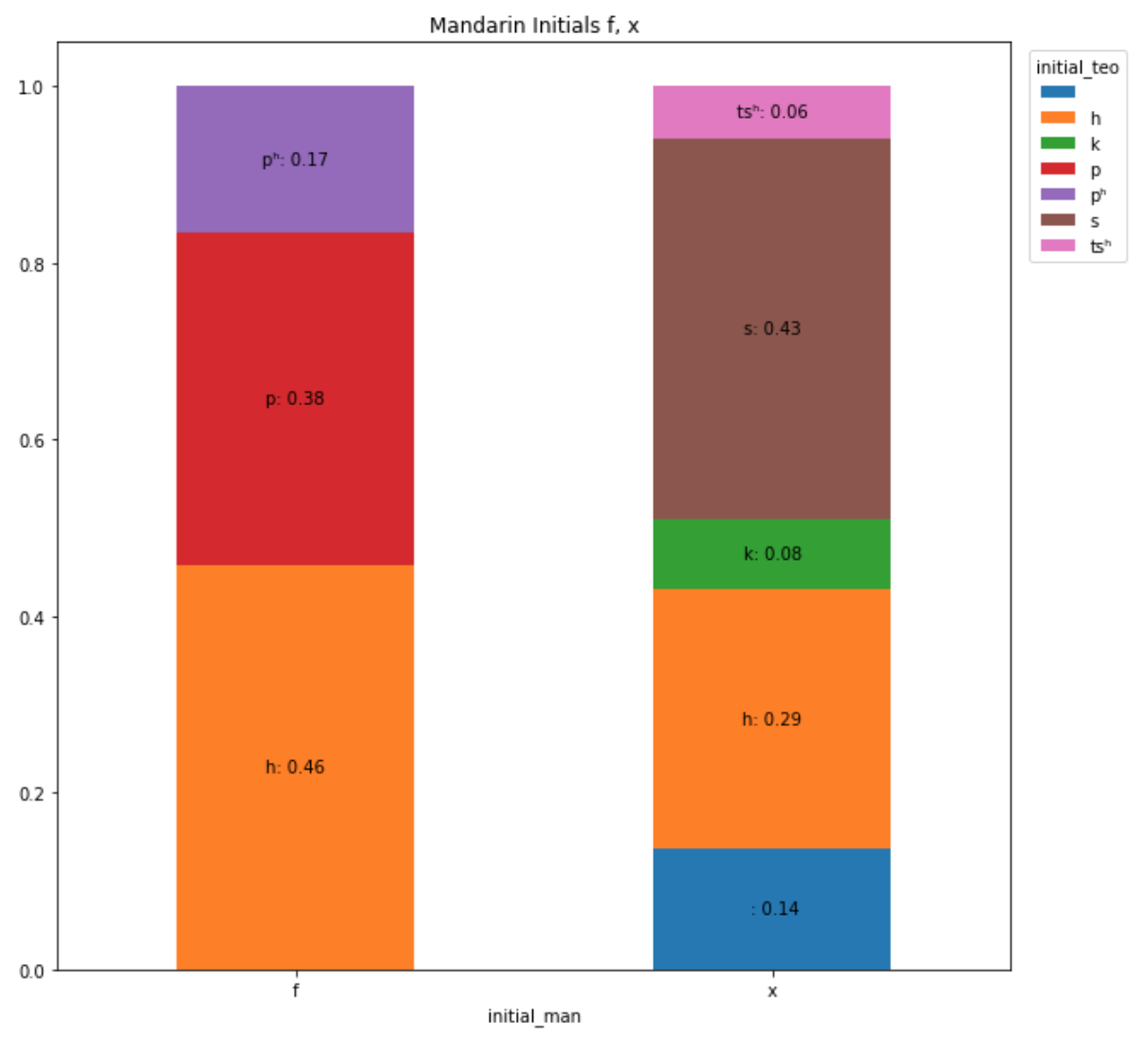

Let’s look at some interesting initials where Mandarin and Teochew’s sound differently.

Mandarin has two voiceless fricatives f and x that does not exist in Teochew. For example,

# f sound in Pinyin

發: (f)a1 - (h)uek21

反: (f)an3 - (h)ueŋ35

粉: (f)en3 - (h)uŋ53

# x sound in Pinyin pronounced as s or h

新:(x)in1 - (s)im33

小: (x)iao3 - (s)ie53

斜: (x)ie2 - (s)ie55

鄉: (x)iang1 - (h)ĩẽ∼33

薰: (x)un1 - (h)uŋ33 # u in xun is actually ü

行: (x)ing2 - (h)aŋ55

People who are native speakers of Teochew often struggle to pronounce the f sound in Mandarin, making the h sound instead (At least for my dad).

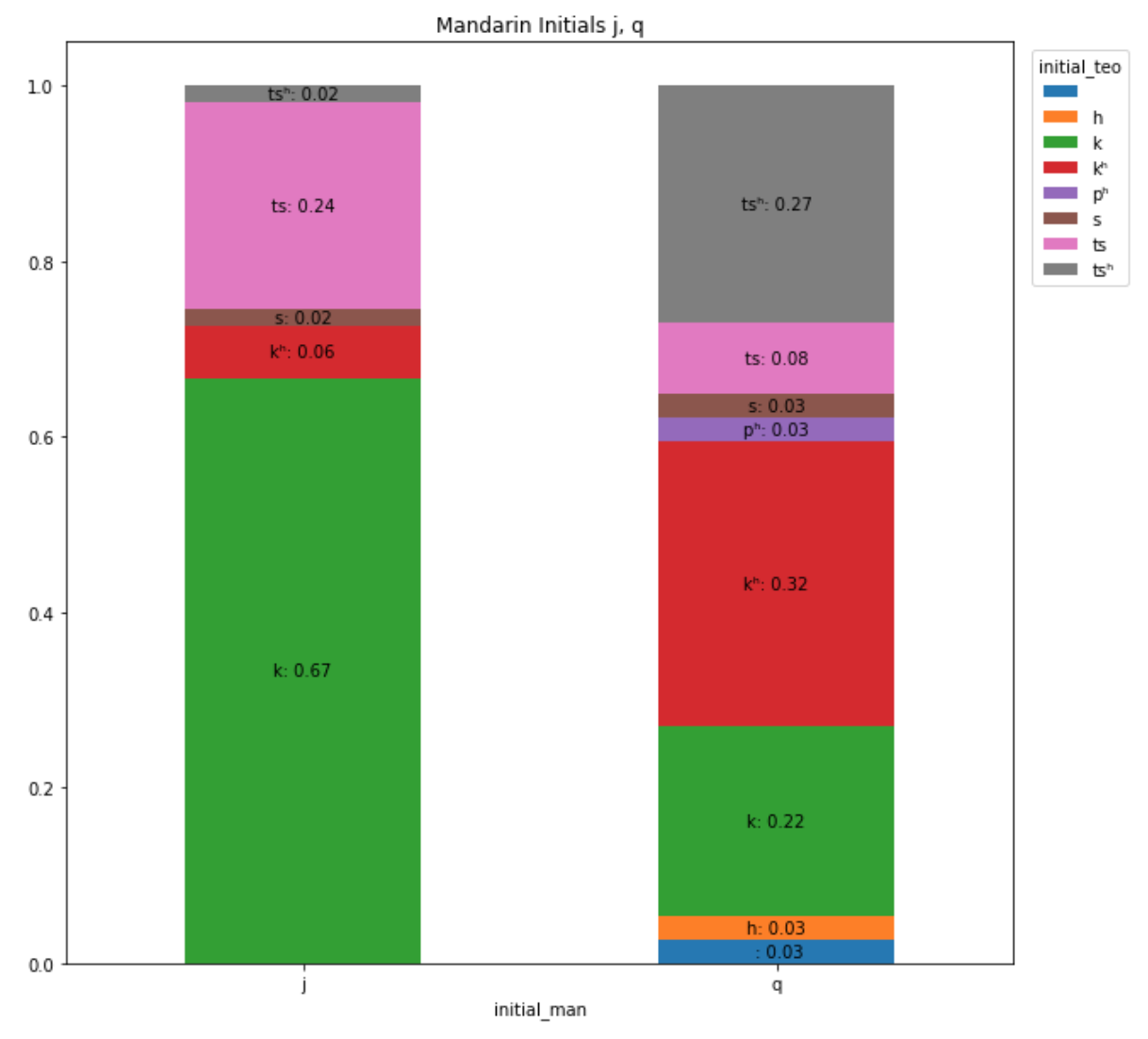

J and q are other groups where the sounds of initials have changed.

From the plot above, we see 67% of the initial j is pronounced as k in Teochew. kʰ accounts for only 6%, is pronounced similar to k, except that the latter forces more air and vibration from the back of our tongue.

On the other hand, 32% of the corresponding Teochew initials to Mandarin q is kʰ, 27% from the sound tsʰ and 22% are formed by k.

Some examples of j and q are shown below:

# j sound in Pinyin

家: (j)ia1 -- (k)e33 角: (j)iao3 -- (kʰ)ak21

甲: (j)ia3 -- (k)aʔ21 键: (j)ian4 -- (kʰ)ĩã∼11

叫: (j)iao4 -- (k)ie213

# q sound in Pinyin

汽: (q)i4 -- (kʰ)i213 淺: (q)ian3 -- (tsʰ)ieŋ53

琴: (q)in2 -- (kʰ)im55 雀: (q)ue4 -- (tsʰ)iaʔ21 # u in que is actually ü

勸: (q)uan4 -- (kʰ)ɯŋ213 橋: (q)iao2 -- (k)ie55

3. Finals

Due to a large number of varieties in the Teochew finals, the correspondence is more irregular. Nevertheless, there are some patterns in the following examples:

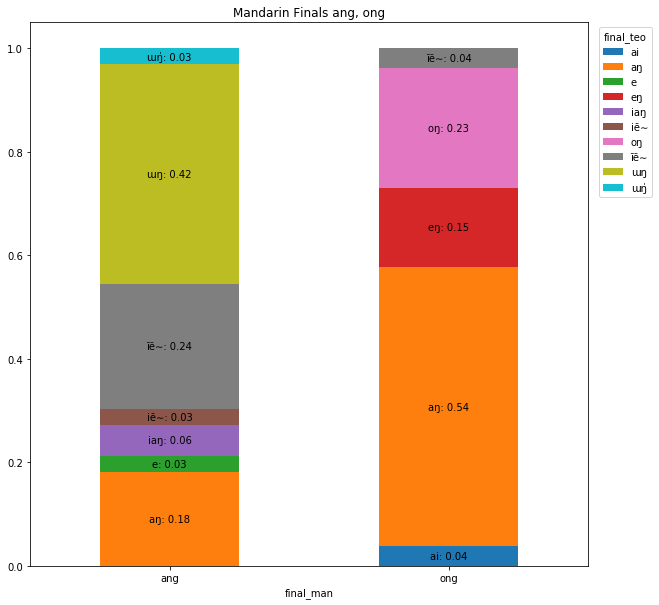

The nasal final is a final that combines a vowel with a nasal consonant -n or -ng. ang and ong are two examples of the back nasal finals.

As seen from the above plots, around one-fifth of the back nasal finals in pinyin map back to the same pronunciation in Teochew (ang to aŋ, ong to oŋ).

However, the majority mapping goes to a different back nasal finals: 42% of Mandarin ang becomes ɯŋ in Teochew while 54% of ong is now aŋ. Some examples are shown below:

# ang in Mandarin

方: f(ang)1 -- p(aŋ)33

湯: t(ang)1 -- tʰ(ɯŋ)33

長: ch(ang)2 -- t(ɯŋ̍)55

# ong in Mandarin

終: zh(ong)1 -- ts(oŋ)33

空: k(ong)1 -- kʰ(aŋ)33

弓: g(ong)1 -- k(eŋ)33

It seems that Mandarin and Teochew have a strong correspondence between back nasal finals.

![]()

Hope you enjoyed the data visualization above!

You can see there is a correspondence between these two languages. Due to the space limits, I only covered a few to illustrate the points. This guide (written in Chinese) is the primary source for me to check out most of the systematic correspondences.

Therefore, my baseline approach is to predict the most frequent Teochew initials, finals, and tones given its Mandarin counterparts.

Another reasonable assumption, on the other hand, considers their interaction. Initials and finals in Teochew combined might limit the number of possibilities of tones that can exist.

Exactly how much is this interaction is left to be found in the analysis.

Proposed Methods

I used both random forests and a one hidden layer neural network as two separate methods compared to the baseline.

Both the random forest and neural network methods assume there are some levels of interactions among initials, finals, and tones.

Since all my features are categorical values, all the input data are converted to one-hot encoding. Teochew initials, finals, and tones are assigned a unique class number within each category.

Random Forest

Random forests are an ensemble tree-based method that predicts the result based on votes from the majority. It has two layers of randomness. 1) For each decision tree, we bootstrap from a portion of (or all of) the training data, having enough sample varieties in the trees. 2) For each node in a tree, we randomly select a subset of features to decide the max split. Based on these two features, random forests outperform many algorithms in the Kaggle competition.

I trained 3 separate random forest classifiers. The first classifier takes in all three input features (initials, finals, and tones), totaling 64 classes, to predict Teochew tones—the second classifier for Teochew initials, and the last for the Teochew finals.

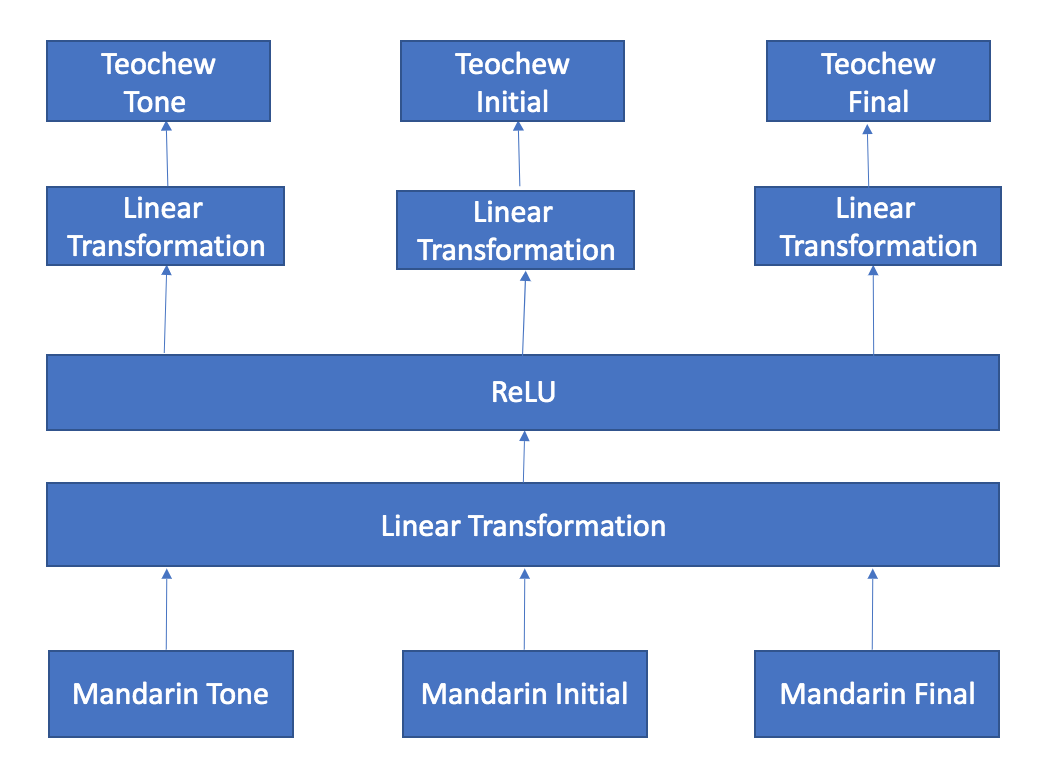

Neural Network

A neural network is flexible in terms of the number of outputs we can have. Therefore, instead of training three separate random forests, I trained one hidden layer neural network to predict all three things at the same time. The architecture of my neural network is defined as follows:

The networks concatenate three vectors of inputs and perform a linear transformation on the joined vector, followed by a rectified linear unit on each neuron. After that, the neurons are mapped to three separate linear transformations to predict multi outputs. The custom loss function is the sum of all three cross-entropy losses for tones, initials, and finals. Based on experience, I chose the number of hidden neurons to be 75% of the input features.

Evaluation

If you have followed through, there must be a question you are curious to find out: how much interaction is among Mandarin initials, finals, and tones?

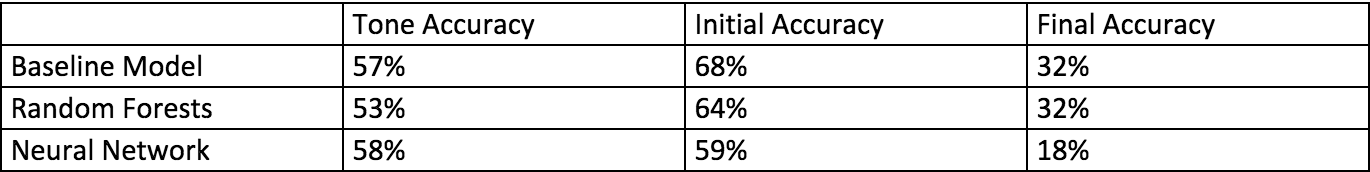

Table below shows the evaluation accuracy for three methods.

The majority baseline performs slightly better than the random forests and neural network methods. We can conclude that in this dataset, there is little evidence to imply an interaction among tones, initials, and finals.

Among all three predictors, initials appear to have the best evaluation score, followed by tones. The low accuracy for finals is expected since some finals in the test set never occur in the training set.

Conclusions

By exploring the relationship between the Teochew and Mandarin languages, we successfully taught a computer to predict Teochew’s linguistic components. Due to the limited data size and noisy features, we are unable to learn the interactions among the components. Future work extends to the relationship of more closely related languages like Cantonese and Teochew. More fined-grained features on Teochew finals and increased dataset size are expected to produce more desirable results.

Anyone who makes their way to the very end of this post, you are now a ga gi nang (our people) ![]()