Master Depth-first Search on Graphs

Recently, I met with a friend who actively interviewed for software engineer roles; I asked him: “was the coding interview hard?” He laughed: “The first company asked me a DFS question, and then the second company also asked about DFS, by then I already gained experience”. He was kind of lucky, but this makes me think: why would companies favor such a simple search algorithm over somthing more complicated, say, dynamic programming?

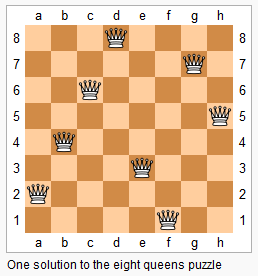

As we know, Depth-first Search (DFS) is a specific algorithm for tree like structure; However, it is not limited to just that. When DFS is combined with backtracking, it can apply to any implicit graphs. A classic application is N-Queens on a chess board.

This blog post will help you understand the basic setting of DFS.

Those You Think are DFS Problems

DFS problems usually have the following characteristics:

- The problem has some sort of graph/tree; graph can be implicit.

- It asks you to find the number of “connected pieces” or “max area of islands”, or simply find cycles in a graph, or a path from one node to another.

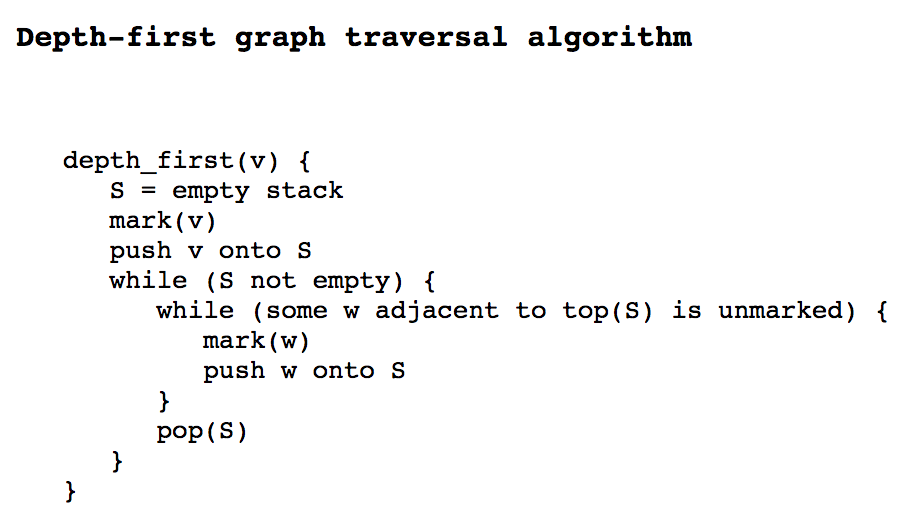

The pseudocode above was taken from here, which uses a stack to hold marked elements. In each iteration, we take from top of the stack, and push one of its unmarked childs (or neighbors) to the stack. We keep doing this until one descendant no longer has marked child; that means, we have reached the end of one path. Now we need to pop off that descendant and go back to its parent node. There might be some other unvisited paths from its parent node.

While this pseudocode is widely taught at school, I prefer another way of representing stack – recursion.

depth_first(v) {

mark(v)

while (some w adjacent to v is unmarked) {

depth_first(w)

}

}

Is Graph Bipartite?

Let’s look at our first DFS problem from leetcode: Given an undirected graph, return true if and only if it is bipartite. graph[i] is a list of indexes j for which the edge between nodes i and j exists. Each node is an integer between 0 and graph.length - 1. An example of input is as follows:

graph = [[1,3], [0,2], [1,3], [0,2]]

Recall that a graph is bipartite if we can split it’s set of nodes into two independent subsets A and B such that every edge in the graph has one node in A and another node in B.

How do we ask the program to split though? Let’s visualize it.

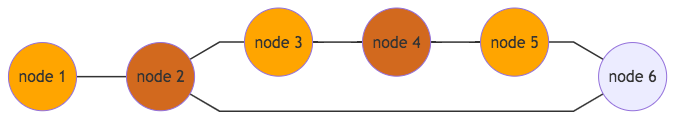

There are five nodes 1 to 5 in the diagram above, with two distinct colors for different subset (assume color orange is for subset A, and color chocolate is for subset B). If the computer starts with node 1, it can assign alternating colors to every node, which leads to a bipartite graph.

Now imagine we add a node 6 to the graph.

When the program traverses from node 5 to node 6, it should have assigned node 6 to subset B (chocolate). However, that means node 6 and node 2 will violate the definition of bipartite.

Note: the arrows are just to show the direction of traversal. The actual graph is undirected

Once we’ve got them sorted out in the graph, it is easy to translate the logic into pseudocode:

# 1 means subset A, while 0 means subset B

depth_first(v, subset=1) {

mark(v)

assign v to subset # subset(v) = 1

while (some w adjacent to v is marked) {

if (subset(w) is equal to subset(v)) {

# the graph is not a bipartite

return False

}

}

# end while

while (some z adjacent to v is unmarked) {

if not depth_first(z, 1-subset(v)) {

return False

}

}

# the graph is a bipartite

return True

}

This solution takes O(n) runtime, at worst, where n is the number of nodes in the graph. Although every node is visited again by its neighbors, the multiplicative factor is just a constant!

Hopefully you enjoyed this blog! Now stay tuned as I will be posting more content in the coming week ![]()