Sentiment Classifier: Beneath the Surface of your Messages

Recently, I worked on a side project which allows me to perform sentiment classification in Chinese text. The program can classify any given sentence as either positive or negative.

I found this idea when I scrolled through the text between me and my boyfriend Bai on Facebook Messenger. Could statistics tell me who’s more optimistic in the relationship?

One way to achieve this is by deciding the text polarity: either positive or negative.

The Data

I did not use any popular Chinese sentiment dictionaries as my training data for two reasons:

First, dictionaries such as ANTUSD contain formal opinion words. However, my own text is causal, leading to a potential distribution mismatch.

-

What is distribution mismatch and why it is bad?

-

Distribution mismatch occurs when training and test set do not come from the same distribution. This can lead to poor prediction results.

-

Second, dealing with negation words is hard. In English, words such as “not”, “but”, can appear anywhere in the sentence and change the sentiment of the entire sentence. Same rule applies to Chinese.

Instead, I found a GitHub repo with manually labeled text from human-computer conversational logs. The author classified each segmented sentence either positive or negative. 11577 labeled instances! That must have taken lots of manpower.

Pseudo-labelling

However, distribution mismatch still exists. Because what a human asks a robot (training set) is still different from what two people’s talking (test set).

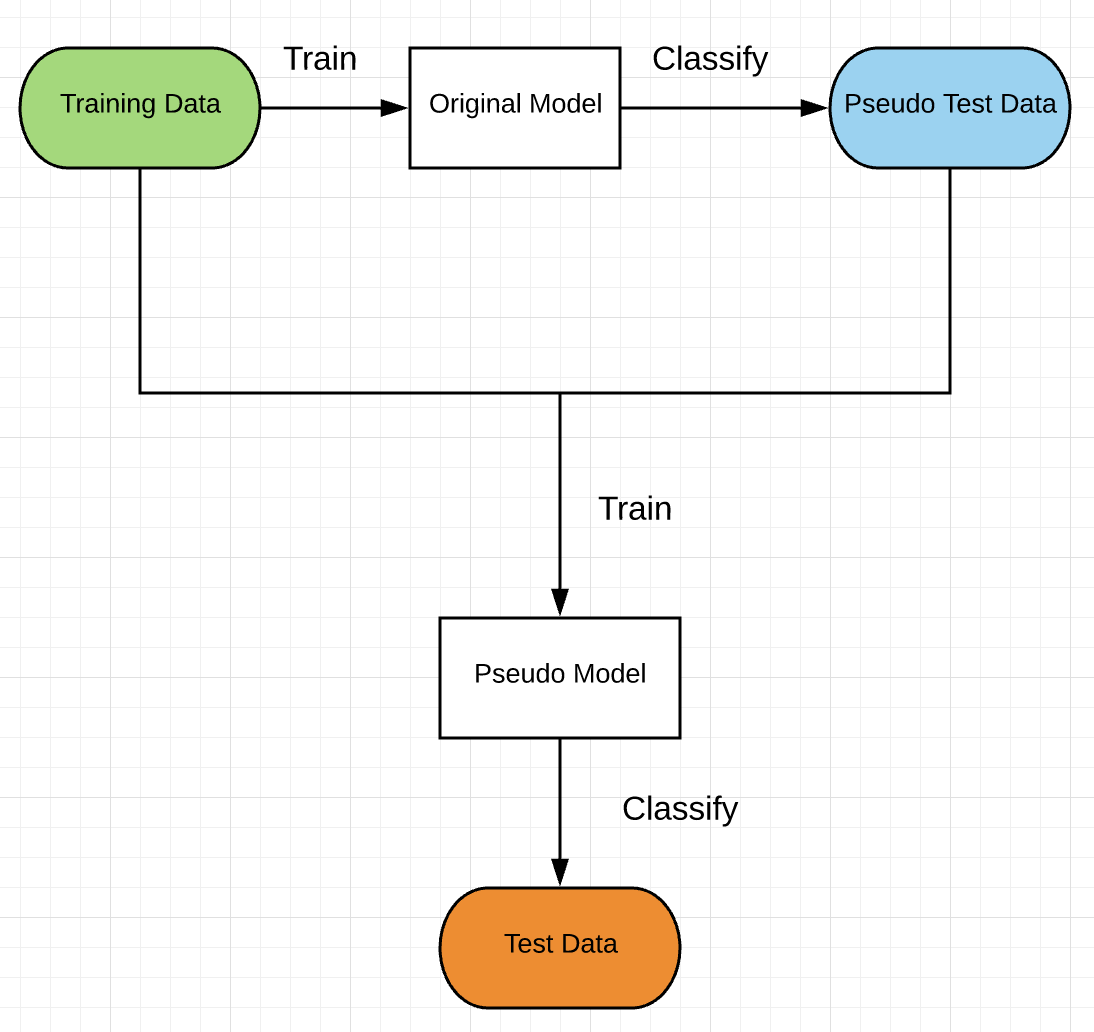

My workaround is to have pseudo-labelling. This method works well when I have labeled training data but not test data. The workflow is shown as below.

First, I trained my model with only the training data I found online. Then the model was used to predict labels for some of my unlabeled data from Facebook Messenger. I called it pseudo test data.

The training data and the pseudo test data were joined together to train a new model. My new model has the same parameters as my original one. Finally, this new model, also called pseudo model, classified the rest of my unlabeled test data.

In a rigorous sense, I should not use the term “test data” for unlabeled samples. However, for simplicity, I will mention “test data” and “pseudo test data” throughout this post.

Someone may ask: What if the predicted label is not right in the first place? Putting it to train would do more “wrong” to the classifier, wouldn’t it? The idea is to have more data even with a little bit of noise. And the model outperformed the one with less data. I will show the results later in this post.

Data Preprocessing

I downloaded about 4000 conversational text from Facebook Messenger. Each message is composed of either several phrases, or no more than three sentences. 70% of those I used as training data in the later stage with pseudo labelling. The rest was my test data.

Unlike English, Chinese words are not separated by spaces. Therefore, I used THULAC for word segmentation to cut my text sentences. It is relatively fast and accurate.

I also removed some common Chinese stop words as they do not contain useful information.

Feature Extraction

Next question is, what kinds of representation to use? The answer is not 42. It ranges from rule-based approaches such as Word2vec, n-grams, to all-in-one models like BERT. I resisted the temptation to use BERT. Wait, do not click the close button yet, I promise to use that one day.

I chose BoW (bag of words), with TF-IDF as the weighting scheme.

TF-IDF filters out common but unimportant words, while only keeping some key words. However, this method would discard context-based information. Unlike paragraphs, my data only consists of independent sentences, so it won’t hurt much.

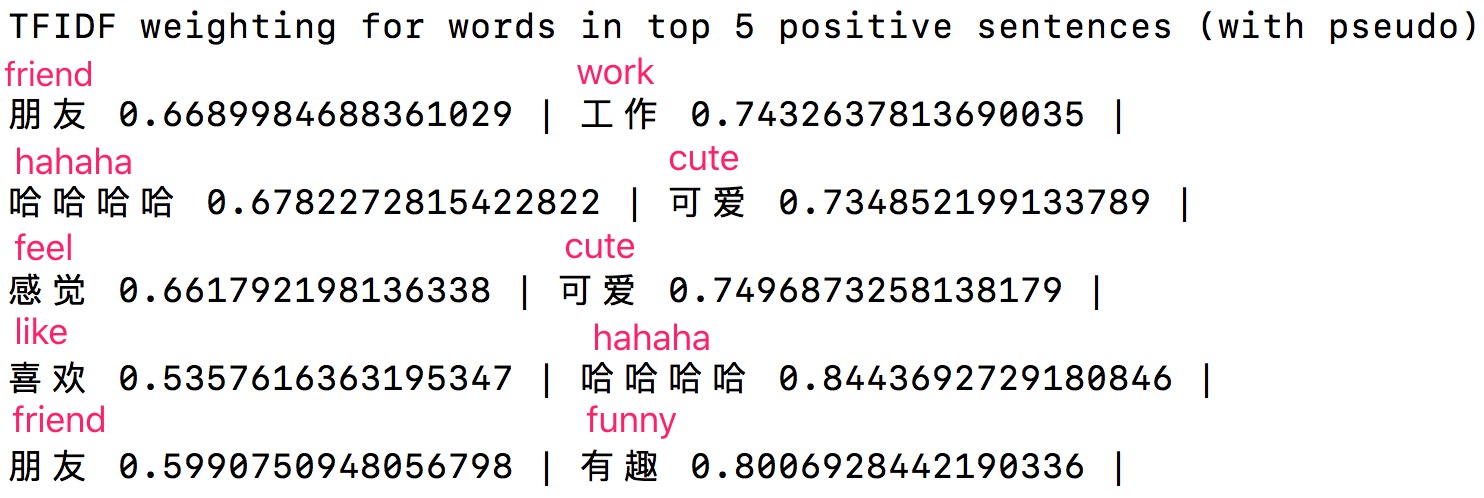

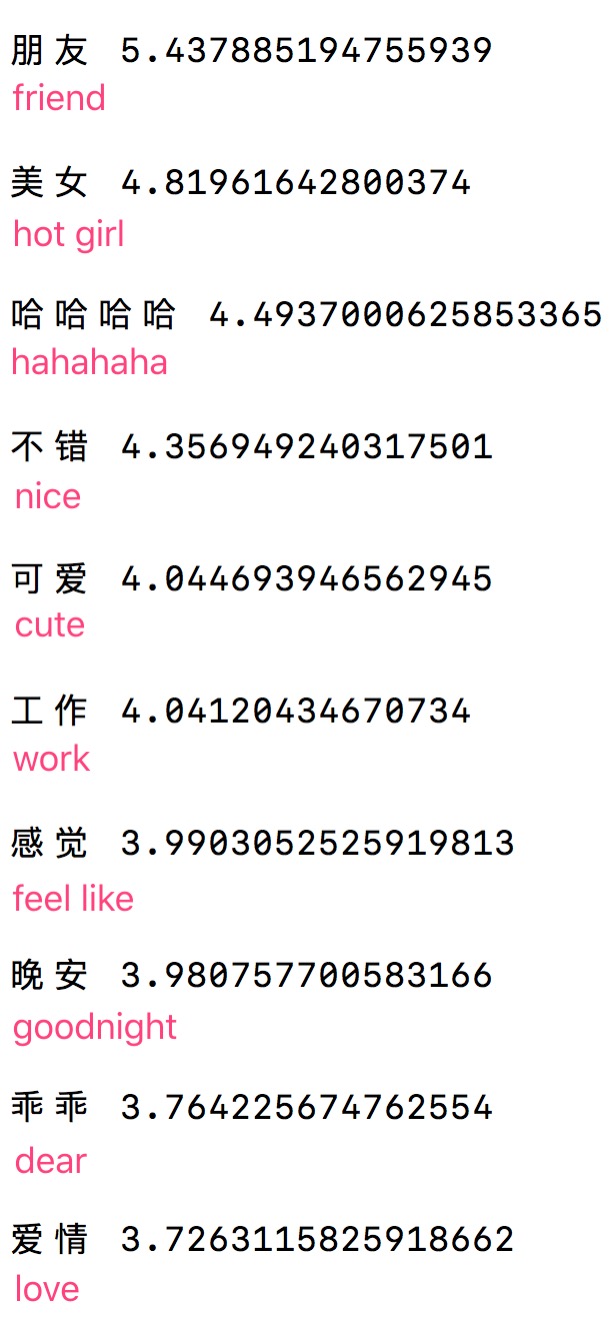

Below shows TF-IDF weighting of words in top 5 sentences with pseudo labeling.

Words that contribute more to positive scores reflect in their literal meanings too!

Logistic Regression

Logistic regression is an effective model for classification problem. And LogisticRegression from scikit-learn comes handy: it not only assigns a 1 (positive) or 0 (negative) label, but only tells me how confident it is with the prediction.

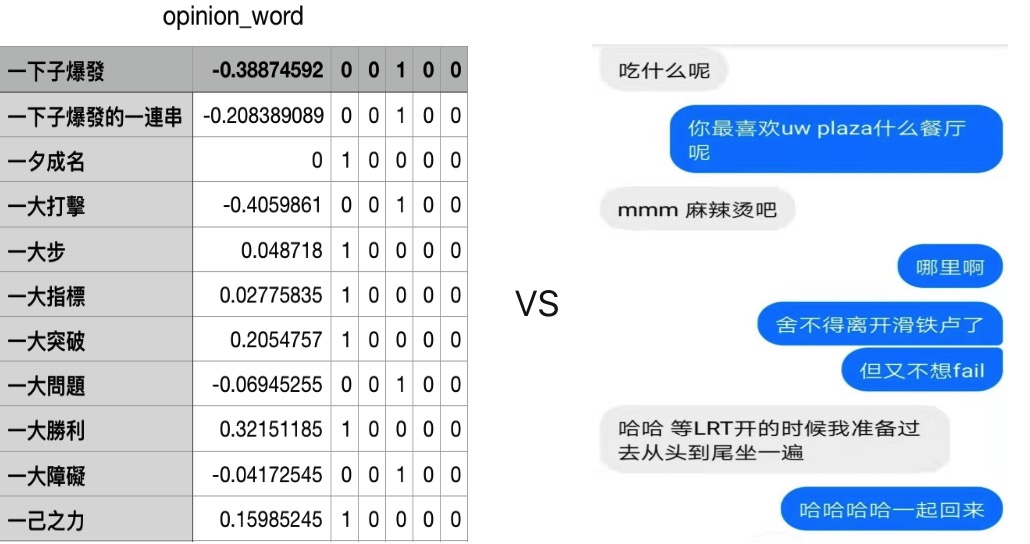

Below is the regression coefficient for 10 most positive words:

Therefore, Logistic regression model is more likely to produce a positive score if the test data contains the above words.

Data Analysis

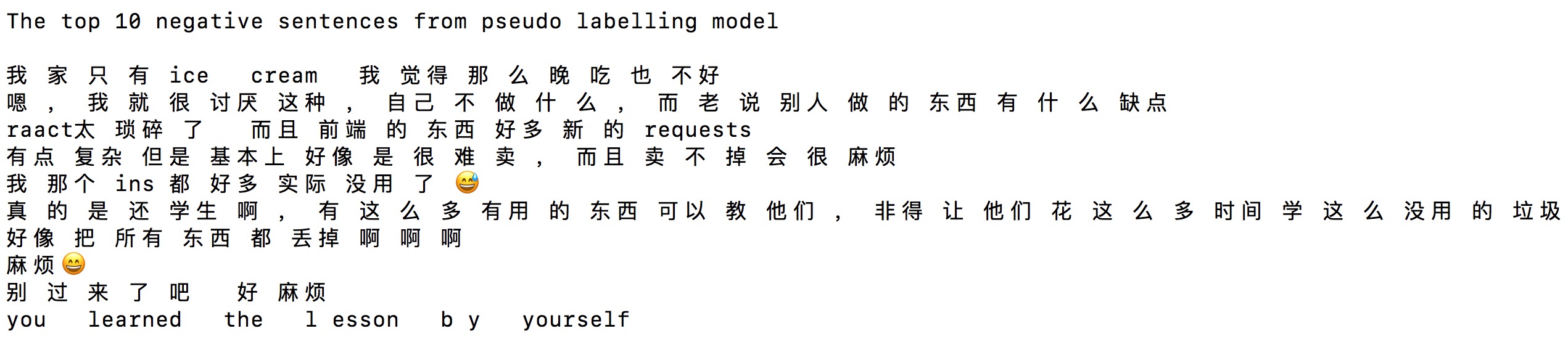

The model can predict well on some test data. For example, below are the top 10 negative sentences based on logistic regression.

Seems like the classifier was learning something. However, in some other cases, it struggled to predict the right label. The model predicted the below sentence as positive.

The sentence has a word “但”(but), which emphrasizes the latter part of the sentence; however, the model gave more weights to “漂亮”(pretty), changing the sentiment as a whole.

Conclusion

By doing this NLP project, I explored the potential of pseudo labelling, which solves the problem of unlabeled data. I also used TFIDF and logistic regression to produce promising results.

It is a shame that we can only eyeball the top positive and negative words. Nevertheless, the method seems to work and serves as a baseline.

Due to time constraint, I removed stickers and emoji in my model. However, they are equally important as words. In the future, I may combine TFIDF and Word2vec for a stronger representation. It may be worth trying CNNs on the dataset with pseudo labelling, with the inspiration of this paper.

Thanks Bai Li for giving me advice to this project and reviewing my blog!

Hope you enjoyed reading this!

Reference

Sentiment Classification with Convolutional Neural Networks: an Experimental Study on a Large-scale Chinese Conversation Corpus, in the 12th International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Security (CIS2016)